As a huge advocate of Transactional Analysis (TA) as a concept, I am going to start sharing tools or elements from it in an easy and understandable way, since I believe that every person can use it. And you don’t have to necessarily be a psychologist to use it, especially for using contracting, which is a subject of today’s article.

TA as a theory was developed by Eric Berne in 1950s. It was purely a method of psychotherapy back then, but really quickly people realized that it can be used in educational and organizational context as well. I use it for my personal development, but also in the organizations that I support, while I teach mostly managers how to be smarter, understand their people better and to know more about why and when employees react in a certain way.

The first tool that I found particularly useful was contracting. I teach it while I can and to whom I can because I see how much it can change relations, ways of communication or the way we are working within a team, when we are more mindful about the structure of how we talk to each other. It prevents people from guessing, wasting time on finding the right person or the right information and playing psychological games. In this article I’ll give you basics about the tool and I’ll answer on a question WHY you should use it.

Let’s get started then.

What is contracting regarding Eric Berne? Levels of contract

Contracting is a tool. It can have different value for every person that uses it, since all of us have different needs, thinking preferences, personality and environment that we grew in or live and work in right now. A contract is an agreement between two (or more) sides, in which each party agrees to do a specific thing. Pretty similar to a regular definition of a contract, i.e. while we are signing a contract of employment, we agree to do a certain task list and the organization agrees to pay us a certain amount of money in exchange for it.

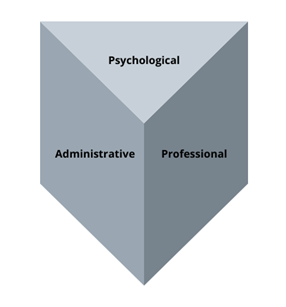

But contracting regarding Berne is something more than just a transaction. It has more layers, there are more details underneath the surface which will have an influence on a person in the future. Berne says there are 3 basic layers of a good contract: administrative, professional and psychological. All 3 need to be covered if we want to talk about a proper contract.

Let’s use the example of a new employee in the team to make it clearer.

On an administrative level we are going to give new employee a contract of employment, information about payroll cycle, bonus system, benefits, working hours, procedures that are valid in this particular organization. Basically, all details that a new employee should know to start a job.

On a professional level we are going to give this new employee ways of working, scope of responsibilities and decision making that she/he can do on their own on their position. Goals, objectives and KPIs, ways and tools of communication, ways and frequency of reporting, as well as 1:1 and team meetings.

On a psychological level we are going to talk about expectations of both sides, needs, past experiences (good or bad) with a decision what to keep, and what to cut from current cooperation. This is the space where we talk about motivation, values and all the thigs that are important while thinking about comfort and efficiency of work.

First two layers are quite simple, intuitive and most of us cover them, more or less. The last one might seem the most difficult, since we need more insight, coaching skills, we need to listen and be open to other person to do it properly. It can be hard, sometimes people don’t want to talk about it, but it is crucial to take it into consideration. Without that we will be relying on guesses and beliefs, instead of facts and real needs that this new person has.

What are the rules of a good contract?

When we think about contracting, there are few elements that we need to take care of every time.

- Both (or more) sides of the contract need to be engaged and agree on what they want to achieve. Before agreeing on something, we need to check with ourselves if we have capacity (i.e. time) for it, to be 100% engaged. If we don’t have enough space, time, money etc. we are going to procrastinate the task, and it’s not fair to the other person and to ourselves as well.

- Fair exchange. It doesn’t mean that we agree on 50:50 division of work. Fairness can mean something else to each person, that’s why we need to establish who is going to cover what, when and what we would like to achieve together at the end of the day.

- Skills. All sides of the contract need to have skills, abilities to do what they agree on. If they need to upskill to do it that’s fine, but we have to establish it while contracting to have a transparency that’s needed to complete the task.

- Compliance. While contracting, we need to take into consideration the law, as well as social or organizational regulations. We also need to think about different perspectives to have a complete context of the situation (i.e. employee and organization – if it is an organizational situation).

If we cover all of those, the contract will be fully transparent, have a good intention and an aim to create a value for engaged parties and/or for somebody else as a result of common work.

Where can I use contracting?

Contracts can be used practically everywhere, that’s the magic of them. This is a really universal tool, and it depends on our individual needs where we want to start trying them out. The areas of usage can be either personal or professional, here are few examples:

- a contract with my roommate about cleaning the apartment,

- a contract with my partner about taking care of kids,

- a contract with a new employee while I am a manager,

- a contract with a colleague to achieve a common goal,

- a contract with a coach for a coaching process,

- a contract with a with a manager while I am an employee for my career path in the organization,

- a contract with a manager while I am a HR person for supporting her/him with a team conflict.

As you can see there are many opportunities, in endless contexts where we can use contracting. The essence of it (besides the elements that were already covered) is:

- what is the goal (what this contract should bring us at the end),

- who are on the sides of contract (2 people or more?),

- how we are going to execute the contract and when,

- what are the conditions of recontracting (if something change, we should be able to act adaptively and react accordingly, i.e. I can make a contract with a new joiner regarding working hours, but while he/she has a child, the circumstances change, and we should talk about those hours one more time to check if it is still applicable).

This is a tool for us, not we are here for the tool. It should support us with having clear, transparent communication and structure around what we do, how and when.

The bottom line

I don’t like to waste my time. I think that it’s too valuable and I don’t have a luxury to spend it on the things that can be done better, faster, simpler or with less energy. Contracting is a tool that can help us to have better, more clear and transparent communication, prevent us from playing psychological games, privately and professionally. It is here for us to stop guessing and start mindfully talk to each other and set together what needs to be done. It is a life changer. Try it and teach others to do the same. The world is going to be a better place thanks to that.

Do you want to know more about TA? Stay tuned for more articles here, visit my Instagram or check out official TA Association.